Giving and receiving feedback is an integral part of working in health care; it is essential in remaining competent to practice ultimately keeping patients safe. I have recently completed an online Assessment for Learning module with QMU and it has helped me to consider the knowledge and skills involved in feedback and as a Practice Educator, how I design learning activities and feedback processes as part of assessment for learning. A particular area that I find interesting is the emotional impact: How can we avoid or minimise the harm that can come with giving and receiving feedback?

When I consider the power dynamics involved, typically the scales will tip in favour of the person giving feedback. In health care, this is likely a practice assessor, supervisor or manager. A learner’s fear of failure is described in the education literature when discussing what makes feedback work (Gibbs, 2015) and failure in health care comes at a high risk. However, when we aim to stay safe or please others, we do not allow ourselves to engage in the type of critical thinking or creative decision making that enables us to be and become confident and capable practitioners.

Algiraigri (2014) argues that feedback practices in clinical settings are suboptimal because they only focus on the teacher. Learners need to be empowered with the skills to receive and use feedback whilst compensating for ‘less than ideal’ feedback delivery when working in a busy clinical environment. When leading on enhancing assessment processes perhaps this is where I should now focus my attention but it feels like there is still something missing. Even if the learner is skilled in feedback, can we really expect them to feel the level of trust needed to give an honest contribution to the dialogue involved in the feedback process. This has led me to explore compassionate feedback in the context of leadership.

I am already familiar with compassionate leadership in health care (The Kings Fund, 2022). Perhaps this is why compassionate feedback feels more meaningful to me as a facilitator of learning in this environment. The Interrogating Spaces (2023) podcast on compassionate feedback uses Grahams definition of compassion; the act of noticing distress or disadvantage in yourself or others with a commitment to take action on it. Compassionate feedback therefore seems social and relational as well as skills based and I wonder if this approach to feedback would therefore have an impact on shifting the power imbalance as an indirect result?

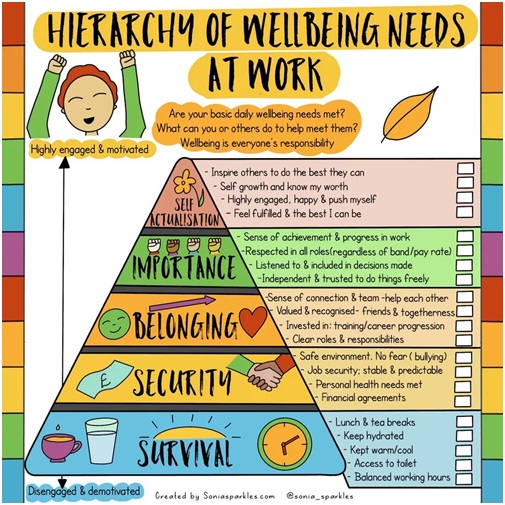

A key component of compassionate feedback is the sense of belonging. Inclusion drives human behaviour. The learner feels valued and respected. Essentially the learner feels like the person giving feedback really cares about their learning. It’s about making space to connect and then being able to be your authentic self in that space. The benefits of regular supervision as part of reflective practice are well recognised within the allied health professions (Scotland’s AHP Position Statement, 2018. HCPC, 2021). The biggest reason given for not engaging with supervision is the time taken out of clinical practice to do it. Yet, when I watch Chris Turner (2019) talk about how “civility saves lives” then perhaps as Evans (2013) suggests, we need to be clearer about what is important as well as what is urgent.

Kumagai & Naidu (2015) ask the question on what does it mean to devote space for those types of exchanges in busy clinical environments i.e. what is this space, how can it be identified or designed? They suggest reflective space is fluid, in that it includes the opportunities and circumstances that happen in the moment as well as within the more formal learning activities, or time set aside for supervision. This makes me think of the everyday conversations we have with each other – all of us, at all levels of practice, in all workplace areas – and how this space can be opportunities to provide compassionate feedback. We still need to create space for this exchange to take place but only for a considered moment.

My action for my own professional development is to understand what reflective space means within the learning environments in which I lead facilitation of learning. This will involve considering who else needs to be involved and how we collaborate to better design spaces that support compassionate feedback as a normal aspect of activity in our everyday practice.

Laura Lennox is an AHP Practice Education Lead for NHS Dumfries and Galloway

References:

Algiraigri, A. H. (2014). Ten Tips for Receiving Feedback Effectively in Clinical Practice. Medical Education Online. Vol. 19. Issue 1.

Evans, C. (2013). Making Sense of Assessment Feedback in Higher Education. Review of Educational Research. Vol. 83. No. 1. pp70-120.

HCPC. (2021). Available at: Supervision. (Accessed 05/12/2023)

Interrogating Spaces. (2021). Compassionate Feedback. UAL Teaching, Learning and Employability Exchange. Season 3. Episode 1. Available at: https://interrogatingspaces.buzzsprout.com/683798/11480939-compassionate-feedback. (Accessed on 02/12/2023).

Scotlands Position Statement on Supervision for Allied Health Professions. (2018). Available at: (Scotland’s position statement on supervision for allied health … (Accessed on 04/12/2023)

The Kings Fund. (2022). Available at: What is compassionate leadership?. (Accessed on 03/12/23)

Turner, C. (2019). When Rudeness in Teams Turns Deadly. Ted Talk. Available at: When rudeness in teams turns deadly | Chris Turner – YouTube. (Accessed on 03/12/2023).