Given that it is the year of the world cup we thought we would change our name to that of a football team. For those of you (Eddie) who don’t follow football PSG stand for Paris Saint Germain and has a catchy ring to it!

Like some of these famous football players my job role as Adverse Events Co-ordinator is just as exciting!! I oversee the whole of NHS Dumfries and Galloway’s Adverse Events and risk.

I also co-ordinate the organisations Significant Adverse Event investigations and reviews and it was at one of the review meetings that I was put forward to write this blog – Cheers Ken!

I love to make the most of every opportunity therefore I thought I would use this blog to share with you some exciting changes you can expect to see over the coming year.

But firstly we would like to make a clear, public commitment to staff that our organisation supports an open and fair culture, by letting you all read a Key statement from our chair and co-chair person, Eddie Docherty and Ken Donaldson (on behalf of Patient Safety Group (PSG))…….

“There is no doubt that over the years there has been a culture of blame in the NHS.

As chair and co-chair of the Patient Safety Group, we would like to see us move to a culture where we learn and improve from any failure.

It is our firm belief, that in a complex system like the NHS, it is often not the practitioner’s fault when things go wrong.

Staff will be treated fairly and supported to identify the failures in the system and improve service delivery.

We require ongoing honest reporting of concerns at the earliest possible stage to do what we can to ensure your working environment is safe. We would therefore ask all healthcare professionals to continue to raise all concerns in the appropriate manner predominantly by using Datix “.

During my first year as adverse event coordinator I found myself being asked two frequent questions, “Who are QPSLG?” and “What do they do?”

New name

Firstly the Quality and Patient Safety Leadership Group also known as QPSLG or “Quiggle Spiggle” have changed their name to Patient Safety Group (PSG for short). We are confident this change of name will give a better understanding to everyone what we do.

Who are PSG?

Let me introduce you to a few of our members…..

Eddie Docherty

As Executive Director of nursing midwifery and allied health professions I chair PSG. I am passionate about pushing the organisation forward as a learning environment, with a key focus on patient and staff safety.

As Executive Director of nursing midwifery and allied health professions I chair PSG. I am passionate about pushing the organisation forward as a learning environment, with a key focus on patient and staff safety.

Ken Donaldson

For the past 8 years I have developed an interest in enhancing patients experience and ensuring staff experience is as good as it can be – which is difficult with current staffing issues and recruitment challenges. I believe my role in PSG is to ensure a balanced and fair approach to all serious adverse events and complaints. We need to focus on learning from error, improving systems and providing robust feedback – an area we are working on to improve. ‘To err is human…’

For the past 8 years I have developed an interest in enhancing patients experience and ensuring staff experience is as good as it can be – which is difficult with current staffing issues and recruitment challenges. I believe my role in PSG is to ensure a balanced and fair approach to all serious adverse events and complaints. We need to focus on learning from error, improving systems and providing robust feedback – an area we are working on to improve. ‘To err is human…’

Andy Howat

My role as the Board’s Health & Safety Adviser involves identifying, helping manage, reduce and control exposure to workplace hazards. With the ultimate aim of reducing the number of incidents, accidents and ill health in the organisation.

I work with teams helping them assess risks, develop risk reduction strategies, instigate changes in working practice, develop and deliver coaching/training, and offer advice on all aspects of workplace safety and occupational wellbeing.

I have been part of the Patient Safety Group for about a year now and I am regularly involved in reviewing significant incidents, considering the staff, patient and organisational affect these have and trying to enable the development of practical and pragmatic ways of reducing the likelihood and consequence but, ultimately the prevention of these incidents.

Stevie Johnstone

“My name is Stevie Johnston and I provide administrative support to PSG by not only co-ordinating the meetings but by working with others throughout the organisation to gather updates on incidents and investigations. My knowledge around adverse events and the investigation process was limited but the group has given me the confidence to ask questions from a different perspective during meetings and the review process. I have recently undertaken Adverse Events Training and look forward to putting this into practice in order to understand why errors happen, how we can stop them from happening again and how we can share learning in order to support others within NHS Dumfries and Galloway”

Linda Mckechnie

As Lead Nurse/Professional Manager, Community Mental Health Services, One of the most important things for me is to always look at what we can learn when things go wrong or don’t go as well as they should. This might be individual learning for staff, learning for teams or services, or learning across the organisation(s). Supporting staff when things go wrong is essential in order to encourage learning and reflection.

As Lead Nurse/Professional Manager, Community Mental Health Services, One of the most important things for me is to always look at what we can learn when things go wrong or don’t go as well as they should. This might be individual learning for staff, learning for teams or services, or learning across the organisation(s). Supporting staff when things go wrong is essential in order to encourage learning and reflection.

Emma Murphy

As Patient Feedback Manager, I regularly support Directorates with high level and complex complaints. These complaints may be linked to adverse events or have other potential patient safety implications. Sitting on the Patient Safety Group allows me to update members on relevant complaints as well as ensuring I have an overview of new and significant adverse events. By building better links between patient safety and patient feedback, we can improve organisation learning and the patient experience.

Joan Pollard

As Associate Director of Allied Health Professions I am the professional lead for AHPs and manage the Patient Services Team and the corporate complaints team.

As Associate Director of Allied Health Professions I am the professional lead for AHPs and manage the Patient Services Team and the corporate complaints team.

I am curious about processes and culture, passionate about quality and love developing people and teams.

Susan Roberts

I am passionate about supporting staff to learn from errors, near misses or complaints to improve care and therefore my role as professional lead on PSG is a priority for me. It’s not always easy for us to reflect when things go wrong but this process, if supported well, not only benefits patients it helps the staff involved too.

Christiane Shrimpton

Associate Medical Director for Acute and Diagnostics, passionate about excellent patient care, keen to use any available opportunity to ensure we improve what we do and learn from situations that have gone well as well as those that have not gone so well.

Associate Medical Director for Acute and Diagnostics, passionate about excellent patient care, keen to use any available opportunity to ensure we improve what we do and learn from situations that have gone well as well as those that have not gone so well.

Maureen Stevenson

As Patient Safety & Improvement Manager I am passionate about making every day an Improvement Day. I passionately believe that creating the conditions for staff and our communities to learn and share together will enable us to together find practical solutions that improve the quality, the experience and the safety of health and care.

As Patient Safety & Improvement Manager I am passionate about making every day an Improvement Day. I passionately believe that creating the conditions for staff and our communities to learn and share together will enable us to together find practical solutions that improve the quality, the experience and the safety of health and care.

Alice Wilson

Deputy Nurse Director; I am enthusiastic about what I do and motivated by seeing things improve. I really want people to be open with service users/patients and to talk with colleagues about lessons they have learned from good and bad experiences so others can reap the reward, do more of what works well and reduce the risk of repeating the same errors.

And me 🙂

What can you expect…….

Learning from Significant Adverse Events (SAEs)

We are producing Learning Summaries from all our SAEs and we plan to share these with each Directorate but we need these to be meaningful, therefore we would love to hear from you about what learning you have taken from SAEs you have been involved with and how you would uses such a summary. Our first one is ready to distribute and should reach you all very soon so watch this space!!!

We are producing Learning Summaries from all our SAEs and we plan to share these with each Directorate but we need these to be meaningful, therefore we would love to hear from you about what learning you have taken from SAEs you have been involved with and how you would uses such a summary. Our first one is ready to distribute and should reach you all very soon so watch this space!!!

Patient Safety Alerts

We have tested a process of distributing a couple of patient safety alerts one about patients being discharged home with cannulas left in situ and one about poor communication around the location of patients with telemetry in situ. The patient safety alerts will come from the patient safety group, are produced as a result of urgent issues arising from SAEs or themes and are designed to make you aware of a potential risk to harm. So far they have been well received; therefore we will continue to produce these. The next one is on route ………

We have tested a process of distributing a couple of patient safety alerts one about patients being discharged home with cannulas left in situ and one about poor communication around the location of patients with telemetry in situ. The patient safety alerts will come from the patient safety group, are produced as a result of urgent issues arising from SAEs or themes and are designed to make you aware of a potential risk to harm. So far they have been well received; therefore we will continue to produce these. The next one is on route ………

Monthly News Letters

We plan to produce a monthly news letter on a “theme of the month“. The newsletters are informed from adverse events reported on DATIX. Our first edition is ready to go and we have a plan for future ones therefore again watch this space……

Plan for the future

We recognise all the hard work from each directorate in relation to managing their significant adverse events therefore we have put together a timetable for each directorate to provide us with their updates to enable us to support adverse event management in a timely and effective manner.

Communication

The Patient Safety Group is contactable via

dumf-uhb.Adverse-Incidents@nhs.net

Emma McGauchie is the Adverse Events Co-ordinator for NHS Dumfries and Galloway

The advantages of providing this service for the patient means that they have a reduced hospital stay and can return home and rehabilitate in their own environment. In certain cases the patient can continue to work whilst receiving IV antimicrobial therapy therefore causing them minimal disruption to their daily life. Psychologically the patient feels happier, eats better, sleeps better and is more likely to recover quicker in their own home.

The advantages of providing this service for the patient means that they have a reduced hospital stay and can return home and rehabilitate in their own environment. In certain cases the patient can continue to work whilst receiving IV antimicrobial therapy therefore causing them minimal disruption to their daily life. Psychologically the patient feels happier, eats better, sleeps better and is more likely to recover quicker in their own home.

Improved quality of life for patients. They eat better, sleep better and generally feel better in the own home environment.

Improved quality of life for patients. They eat better, sleep better and generally feel better in the own home environment.

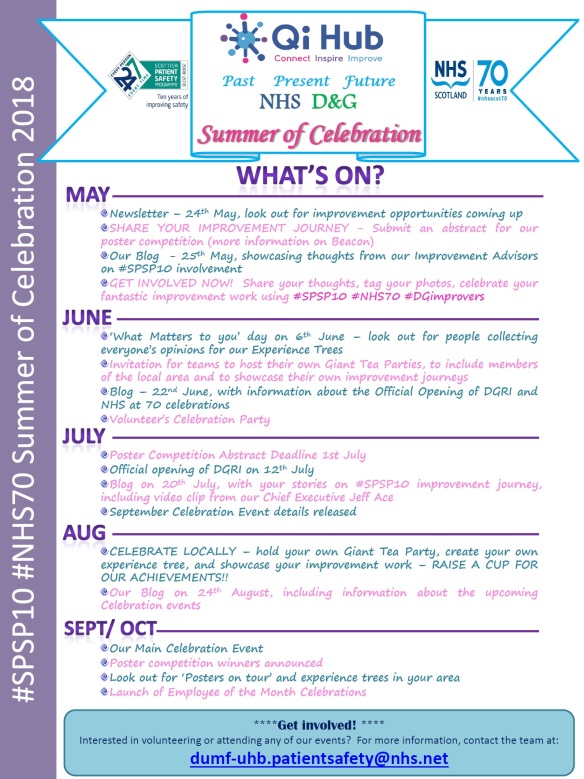

The QI Hub is a creative space where you can connect with others throughout health & social care, people with a passion to make a difference. Thinking space, away from the hustle & bustle that is daily life!! Come and find a supportive network of colleagues, share experiences and learning. Choose from a library of resources and practical tools to help structure your improvement projects and explore development and coaching opportunities.

The QI Hub is a creative space where you can connect with others throughout health & social care, people with a passion to make a difference. Thinking space, away from the hustle & bustle that is daily life!! Come and find a supportive network of colleagues, share experiences and learning. Choose from a library of resources and practical tools to help structure your improvement projects and explore development and coaching opportunities. Building capability and capacity to lead improvement is vital, it empowers people and teams to own change; one resource available is a locally delivered Scottish Improvement Skills Programme. To illustrate how this is already having impact Wendy Chambers, who has recently graduated from Cohort 1, shares her reflections.

Building capability and capacity to lead improvement is vital, it empowers people and teams to own change; one resource available is a locally delivered Scottish Improvement Skills Programme. To illustrate how this is already having impact Wendy Chambers, who has recently graduated from Cohort 1, shares her reflections. Being surrounded by similar and like minded people; learning from each other, sharing ideas, both the things that go well and the things that fail – I’ve come to appreciate that this support is essential to the process of implementing and testing change ideas. Because when I go back out into the real world, with all its pressures and realities, the natives won’t necessarily be as welcoming or receptive to my “bright ideas” and things won’t feel as cosy. So now I won’t be alone, I’ve found my tribe, I’ve found support.

Being surrounded by similar and like minded people; learning from each other, sharing ideas, both the things that go well and the things that fail – I’ve come to appreciate that this support is essential to the process of implementing and testing change ideas. Because when I go back out into the real world, with all its pressures and realities, the natives won’t necessarily be as welcoming or receptive to my “bright ideas” and things won’t feel as cosy. So now I won’t be alone, I’ve found my tribe, I’ve found support.